CLAUDIA STEINBERG: It’s been a few years since you told me about your research in the former GDR – about a forgotten small town and the struggling people stranded there, about the good citizens and the rebels. As a young man, you were determined to live among the poorest, and you took on physical labour, even in the mines. Kafka wrote that he never desired to be around the victors, and you also seem to avoid them, hanging out with the losers who play leading roles in your novels. How did you go about your research into that forgotten zone of the town you call Kana, not too distant from the real medieval town of Kahla, right next to the Autobahn? Did you meet people in bars or at the snack stand? How did you engage with them, and how did they respond to you?

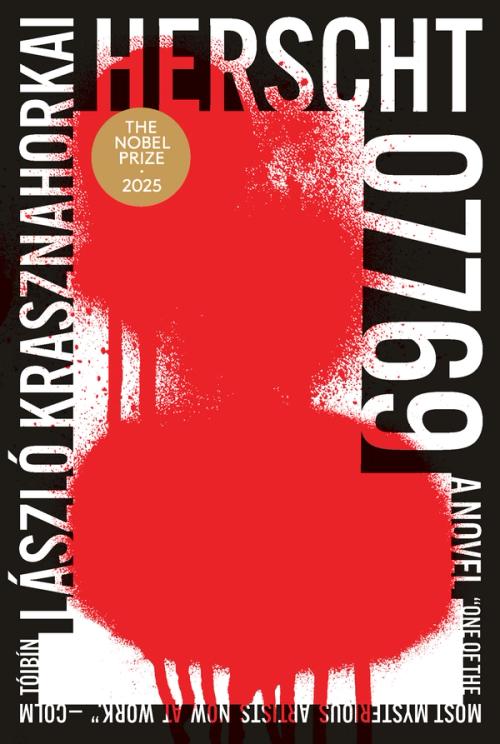

LÁSZLÓ KRASZNAHORKAI: It all began when I said to myself: forget about literature, especially “serious” literature – serious readers have been deserting us in droves, it’s all pointless – it’s time I accomplish something sensible before my life is over: I must, at last, write a book about Johann Sebastian Bach. Ever since my boyhood he has been part of my every day and my feast days; I have never encountered art more sublime than his. This sublime greatness, this vast, varied oeuvre, this ethereal music that casts light – retroactively, as well as prospectively – upon the place we arrive when art reaches its limits, has always made me think about just what these limits of art are, and whether there is anything beyond these limits. I was prepared to compose a personal, yet thoroughly documented and accurate account of Bach’s life, and therefore I researched every scene, every locus, and then I set off to travel and survey each locale, because above all I wanted to get to know the places where he lived; I wished to walk where he had walked, go-sitstand- sleep-eat-and-drink where he had. I started out in Thuringia. I sojourned for some time at his birthplace at the former mill that had belonged to one of his ancestors, at the places where he received his schooling, at the various way stations of his career. I still did not know what shape my planned book about him would take when, one day in a small town, a young man of gigantic stature appeared by my side, as if he had been waiting in some corner for a long time for my arrival, so that he could establish contact with me at last. I have had similar encounters in my life before, and I’m not the least bit surprised that I am the only one who seems to see these characters. They will tell me about a life-changing event, and they will say the one sentence that, as it were, has been bequeathed to them. And they in turn confide it to me, on the basis of a trust that I still find inexplicable. That was what happened in this small town in Thuringia: this young man turned up by my side, and that was the end of the Johann Sebastian Bach book I had been planning. Because the particular fate narrated to me by that young man – after he had introduced me to his local haunts, to his favourite byways, to the weird characters in his life – the fate that he revealed to me via a single sentence was so significant that I at once felt it was too important not to be written. It would be more precise if I were to say that this was what I ended up writing down. Because the words came by themselves, as if they had already been composed in advance, and my task was simply, as it turned out, to merely set them down. That was how Herscht 07769 was born.

Read the rest of László's TANK interview here.

Published