Back in the year of 1847, a group of French scholars sailed aboard the schooner La Gosse to the mouth of the Amazon River. Their goal was to study the flora and fauna of the region, and upon their return present a long and exhaustive paper to the Institut des Hautes Sciences Tropicales de Montpellier.

At the end of that year, the La Gosse anchored in Manaus and, in six dugouts carrying six scholars each, the thirty-six scholars—for such was their number—headed upriver.

By mid-1848 we find them in the village of Teffé, and at the start of 1949, setting out on an excursion down the Juruá River. Five months later they have returned to the village, now towing two more dugouts loaded with curious zoological and botanical specimens. Immediately thereafter they continue their expedition down the Marañón, and on January 1, 1850, they stop and set up camp on the shores of that same river, in the village of Tabatinga.

Of those thirty-six scholars, I personally am interested in only one, which does not for an instant imply that I disregard the merits and learning of the other thirty-five. This one is Monsieur le Docteur Guy de la Crotale, fifty-two years old at the time; plump, short, with a great red beard, kindly eyes, and a rhythmic way of speaking.

I am utterly ignorant of Doctor de la Crotale’s merits, and of his knowledge I haven’t the slightest notion (which does not, of course, deny the existence of either). Regarding his contribution to the famous report presented in 1857 at the Institut de Montpellier, I am absolutely uninformed, and I haven’t the slightest idea what his long years of labor in the tropical jungles with the aforementioned scholars entailed. None of which negates the fact that Doctor Guy de la Crotale interests me to the utmost degree. Here are the reasons why:

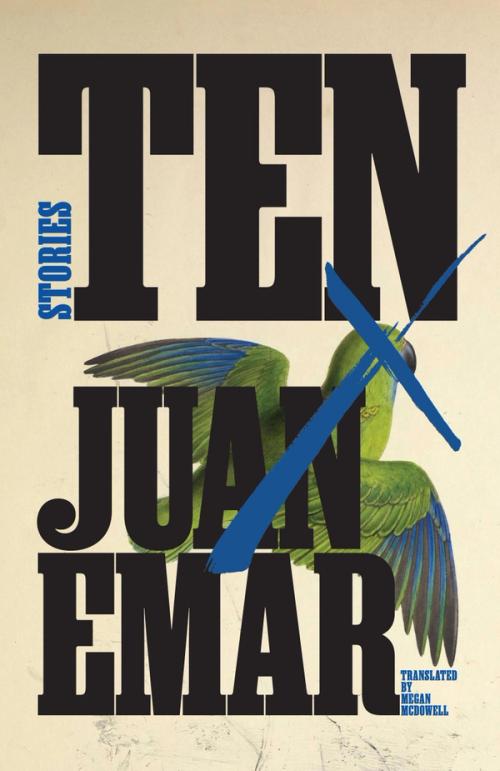

Monsieur le Docteur Guy de la Crotale was an extremely sentimental man, and his sentiments were focused, above all, on the various birds that populate the skies. Among all these little birds, Monsieur le Docteur felt a marked preference for parrots; once the expedition was settled in Tabatinga, he obtained his colleagues’ permission to adopt a specimen, care for it, feed it, and even bring it with him back to his country. One night, while all the parrots of the region were curled up asleep, as is their habit, in the leafy treetops of the sycamores, the doctor left his tent, and—striding among the trunks of birches, crabwoods, dipterocarps and chinaberry trees; trampling maidenhair, damiana, and peyote under his boots; getting tangled up in the stems of lattice moss and periwinkle; his nose smarting from the stench of the mangapuchuy fruit and his ears from the creaking of the purging buckthorn trees—on that hazy moonlit night, the doctor reached the base of the tallest sycamore and climbed stealthily up, and with a well-timed dart of his hand, availed himself of a parrot.

The bird thus captured was completely green save for beneath his beak, where two stripes of bluish-black down adorned him. He was medium-sized, some eighteen centimeters from head to the base of the tail, which extended another twenty centimeters, no more. As this parrot is the center of the story I’m going to tell, I will give a few details on his life and death. Here goes:

He was born on May 5, 1821. That is, at the precise moment when his egg cracked open and he began his life, far, very far away, off on the abandoned island of Santa Elena, the greatest of all Emperors, Napoleon I, was dying.

De la Crotale brought him to France, and from 1857 to 1872 he lived in Montpellier, carefully ministered to by his owner. But in 1872, the good doctor died. The parrot then became the property of the doctor’s niece, Mademoiselle Marguerite de la Crotale, who two years later, in 1874, entered into marriage with Captain Henri Silure-Portune de Rascasse. This matrimony was barren for four years, but in the fifth was blessed by the birth of Henri-Guy-Hégésippe-Désiré-Gaston. From the tenderest age, this boy showed artistic inclinations—perhaps he inherited the old doctor’s refined sentimentality—and of all the arts, he had an indisputable preference for painting. And so it was that when he arrived in Paris at the age of seventeen—for his father had been assigned to the capital’s garrison—Henri-Guy entered the École des Beaux-Arts. After taking a degree in painting, he devoted himself almost exclusively to portraits, but then, keenly influenced by Chardin, he began dabbling in large still lifes that included a few live animals. The house cat, posed amid various foodstuffs and kitchen utensils, went under his brushes; then the dog had his turn; the chickens and canary had theirs; and on August 10, 1906, Henri-Guy sat before a large canvas, his subject atop a mahogany table: two flowerpots with a variety of flowers, a lacquer trunk, a violin, and our parrot. However, the fumes from the paint and the strain of posing began to wear on the bird’s health, and so it was that on the 16th of that month he let out a sigh and passed away—at the very instant when the most terrifying of earthquakes battered the city of Valparaíso and brutally punished the city of Santiago de Chile, where today, June 12, 1934, I write in the silence of my library.

The noble parrot of Tabatinga, captured by the sage professor Monsieur le Docteur Guy de la Crotale and dead on the altar of the arts before the painter Henri-Guy Silure-Portune de Rascasse, had lived for eighty-five years, three months, and eleven days.

May he rest in peace.

But he did not rest in peace. Henri-Guy had him tenderly embalmed.

The parrot remained embalmed and mounted on a fine ebony pedestal until the end of 1915, when it was learned the painter had died heroically in the trenches. His mother, widowed seven years earlier, thought to travel to the New World, and before setting sail, she auctioned off much of her furniture and possessions. Among these was the Tabatinga parrot.

It was acquired by old père Serpentaire, who kept a store at number 3 rue Chaptal that sold bric-a-brac, antiques of little value, and taxidermy. And there the parrot remained until 1924 without awakening a glimmer of interest in his personage. But that was the year things would change, and here I’ll relate the manner and circumstances by which they did:

In April of that year I arrived in Paris, and, along with various friends from back home, dedicated myself night after night to the most roaring and joyful revelry. Our preferred neighborhood was lower Montmartre. On rue Fontaine, rue Pigalle, boulevard Clichy, or the place Blanche, there was no dance hall nor cabaret that did not count us among its most fervent customers. Our favorite was, without a doubt, the Palermo on the aforementioned rue Fontaine, where, between one jazz band and the next, an Argentine orchestra played tangos that were sticky as caramel.

We would lose our heads at the first notes from the bandoneon, champagne would flow down our gullets, and by the time the first singer—a leathery baritone—broke into song, our excitement verged on madness.

Among all those tangos, there was one for which I had a great predilection. Perhaps the first time I heard it—or better yet, “noticed it”; or even better, “isolated it from the rest”—a new feeling shivered through me, a new psychic element was born within me, and, as it burst open and spread outward—like the parrot breaking its eggshell and stretching its wings amid the great sycamore trees—found, in the languid notes of that tango, the matter in which it could develop, strengthen, and endure. A coincidence, a simultaneity, no doubt about it. And although that new psychic element never did enlighten my conscious mind, as those chords broke out I knew with my entire being, from hair to toes, that they—the chords—were full of vivid meaning for me. Then I would dance holding her—whoever she was—tight, with sensuality and tenderness, and I would feel a vague pity for anyone who was not me, rapt, entangled with her and my tango.

The leathery baritone of the Palermo sang:

I have seen a green bird

in rosewater bathing.

And in a crystalline vase

a carnation whose petals are falling.

“I have seen a green bird . . .” That was the phrase—hummed at first, then only spoken—that expressed all feeling. I personally used it for everything, and it always fit with admirable precision. My friends in commiseration adopted it too, filling it with anything around that seemed ambiguous. This phrase was also a kind of code word in our nocturnal conspiracies, and it spun out a web of understanding pliant enough to accommodate every possibility.

And so, if one of us had a great piece of news to share, a success, a conquest, a triumph, he would rub his hands together and exclaim with a radiant face, “I have seen a green bird!”

If a concern or unpleasantness were to loom over him, in a low voice, with suspicious eyes and frowning mouth, he would tell us, “I have seen a green bird . . .”

And so on. Really, we needed nothing else to understand each other; we could express anything we wanted, sink into the subtlest folds of our souls, without needing to avail ourselves of any other words. And life, expressed in this way, with such compression and abbreviation, took on for us a peculiar facet and formed a second life that ran parallel to the first, sometimes clarifying it, sometimes confusing it, and often caricaturing it with such sharp acuity that not even we ourselves could fully and deeply understand where and how it came about.

And, quite often, especially when I was at home and alone after our carousal, I would be hit by an uncontrollable peal of laughter if I merely said to myself, “I have seen a green bird.”

And if at that moment I was looking, for example, at my bed, my hat, or at the rooftops of Paris out the window, and then glanced at the tips of my shoes, the internal tickle of my laughter would rise, and would again cast over all my fellow men a drop of pity, of disdain, even, at the thought of how unhappy they all are, all those who have never even once been able to reduce their existence to a single phrase that includes, encompasses, condenses—even fructifies—everything.

In truth, I have seen a green bird.

And in truth, I am chuckling a little right now, and I can remember and understand why one might feel sorry for humanity.

One day in October I went out reveling in Montparnasse. I visited various bars in the evening and boîtes at night, and after a succulent repast I went back home with a dizzy head, a full stomach, and liver and kidneys working at full steam.

The following day, when my friends phoned at seven in the evening to plan our carousing, my nurse told them it would be utterly impossible for me to join them that night.

They made the rounds at all our favorite spots, and, what with all the champagne, dancing, and dining, they were caught unawares by the dawn, and then by a magnificent autumn morning.

Arm in arm, intoning the songs they had heard, hats pulled down over their eyes or ears, they went down rue Blanche and turned down rue Chaptal in search of rue Notre Dame de Lorette, where two of them lived. When they passed before number 3 of the second aforementioned street, père Serpentaire was just opening his little shop, and there in its window, before my friends’ astonished eyes, rigid atop its big ebony pedestal, was the green bird of Tabatinga.

One of them cried out, “Men! The green bird!”

And the others, more than surprised, were afraid that this was an alcoholic vision, or the very embodiment of their constant obsession. They repeated in soft voices, “Oh . . . the green bird . . .”

A second later, normality returned and they rushed into the store as one, demanding to take immediate possession of the bird. Père Serpentaire asked for eleven francs in exchange, and those good friends, moved to the point of tears by their discovery, paid him double, depositing a sum of twenty-two francs into the confounded man’s hands.

Then their minds returned to their absent companion, and they headed for my house in lock step. They rollicked up the stairs, to the outrage of the concierge, then knocked at my door and delivered the relic to me. And all of us, in a chorus, sang:

I have seen a green bird

in rosewater bathing.

And in a crystalline vase

a carnation whose petals are falling.

The parrot of Tabatinga took its place on my worktable, and there, his glass gaze resting upon the portrait of Baudelaire I’d hung on the opposite wall, he kept me company during the four years I remained in Paris.

At the end of 1928 I returned to Chile. Snugly packed in my suitcase, the green bird crossed the Atlantic once again, passed through Buenos Aires and the pampas, climbed the Andes and tumbled down the other side with me, reaching the Mapocho Station on January 7, 1929. Its glass eyes, accustomed to the poet’s image, curiously took in the low, dusty patio of my house and then, on my desk, a bust of our hero Arturo Prat.

It spent that whole year in peace, and the following year as well. Then, with a nocturnal cannon shot, the year of our lord 1931 began.

And here a new story begins.

On that very January 1—in other words (perhaps a superfluous detail, but, in the end, it has come to my mind), 84 years after Doctor Guy de la Crotale’s arrival in Tabatinga—my uncle José Pedro came to Santiago from the salt flats of Antofagasta and, as there was a guest room in my house, asked my permission to occupy it.

My uncle José Pedro was a learned man, burnished by labors of the imagination, who considered it his most sacred duty to give advice to the youth in the form of long lectures, especially if one of his nephews numbered among the ranks of said youth. Living in my house struck him as a precious opportunity, because—though I don’t know how—news of my constant carousal in Paris had reached his ears. Every day during our lunches and every night after dinner, my uncle, speaking slowly, said horrible things about Parisian nightlife, and admonished me for having spent so many years taking part in it, rather than the Paris of the Sorbonne and its environs.

The night of February 9, sipping coffee in my study, my uncle asked me suddenly, pointing a trembling index finger toward the green bird, “What’s with that parrot?”

In a few short words I told him how it had come into my hands after my best friends had a raucous night of fun that I had missed, because the previous day I had ingested enormous quantities of food and various alcohols. My uncle José Pedro pierced me with an austere gaze, and then, turning his eyes to the bird, exclaimed, “Vile creature!”

That was it.

It was the trigger, the cataclysm, the catastrophe. It was the end of his destiny and the start of a complete reversal in mine. It—as I observed with a lightning-quick glance at my wall clock—occurred at 10:02 and 48 seconds on that fatal February 9 of 1931.

“Vile creature!”

As the last echo of the final “-ure” faded away, the parrot spread its wings, flapped them with vertiginous speed, and, with its ebony pedestal still stuck to its feet, took flight and shot across the room like a projectile, smashing into poor uncle José Pedro’s skull.

Upon impact—I remember it perfectly—the pedestal swung like a pendulum and its base—which must have been pretty dusty—struck my uncle’s big white tie, smudging it. At the same time, the parrot cleaved his bald spot with a violent peck. His forehead cracked, gave way, opened up—and from the crack, just as lava flows, swells, surges, and spills from a volcano, so flowed, swelled, surged, and spilled the thick gray matter of his brain, and several trickles of blood slid over his forehead and down his left temple. Then the silence that had fallen when the bird began its flight was filled by the most horrible shriek of terror, leaving me paralyzed, frozen, petrified, since I had never imagined that any man could ever scream in such a way, much less my good uncle, with his slow and rhythmic speech.

But an instant later, my vigor and my conscience came surging back to me, and I picked up an old copper mortar and lunged toward them, ready to destroy the evil bird with one blow.

Three leaps and I raise the weapon, ready to let it fall upon the creature in the very moment it was about to thrust its beak in a second time. But when it saw me it stopped, turned its eyes toward me, and with a slight movement of its head, it hastened to ask me, “Mr. Juan Emar, could you do me a favor . . . ?”

And I, naturally, replied, “At your service.”

Then, seeing I was paralyzed again, the bird dealt its second blow. Another hole in the skull, more gray matter, more trickles of blood and another shriek of horror, though more subdued now, weaker.

I again recover my sangfroid, and with it, a clear understanding of my duty. Up goes my arm and the weapon. But the parrot—again—looks at me and speaks—again, “Mr. Juan Em . . . ?”

And I, so as to finish quickly, “At your ser . . .”

Third strike of the beak. My uncle lost an eye. The parrot used his beak like a dessert spoon to scoop it out and then spit it at my feet.

My elder’s eye was perfectly round except at the point opposite the pupil, where it had something like a little tail that immediately brought to mind the agile tadpoles that populate the swamps. From this little tail emerged a very thin scarlet thread that led from the floor up into the empty eye cavity, and that, with the old man’s desperate flailing, stretched, contracted, trembled, but did not break; the eye, as if adhered to the floor, did not move. This eye was, I repeat—with the exceptions I’ve noted—perfectly spherical. It was white, white like a marble ball. I had always imagined that eyes—especially old men’s eyes—would be slightly brownish in back. But no: white, white like a marble ball.

Through this white ran graceful, subtle, very fine lacquer veins that, mingling with other, even finer veins of cobalt, formed a wonderful filigree, so marvelous that it seemed to move, to glide atop the damp white surface and, at times, even slip off into the air like an illuminated, airborne spiderweb.

But no. Nothing moved. It was an illusion born of the desire—quite legitimate, it must be said—for so much beauty and grace to grow, take on a life of its own and rise up, to recreate vision and its multiplied forms, or the soul with its astonishing realization.

A third scream brought me back to my duty. Scream? Not so much. A hoarse groan; that is, a groan that was hoarse but sufficient, as I’ve said, to return me to the path of duty.

A leap, and the mortar whistles in my hand. The parrot turns, looks at me, “Mr. Ju . . . ?”

And I, hastily, “At your . . .”

An instant. I stop. Fourth beak-blow.

This one struck at the top of his nose and ended at its base. That is, sliced it off completely.

My uncle, after this, was turned into an appalling spectacle. At the top of his head, from two craters, boiled the lava of his thoughts; the scarlet thread vibrated in his empty eye socket; and in the triangular hole left in the middle of his face by the loss of his nose, a coagulation of thick blood appeared and disappeared, driven out and back in by his panting breath.

Now there was no more screaming or groaning. His one remaining eye, behind his drooping eyelid, could only shoot me a pleading look. I felt it pierce my heart and flood it with all the tender memories going back to my childhood and tying me to my uncle. Before such sentiments I hesitated no more, and lunged frantically and blindly. As my arm fell, a whisper reached my ears, “Mr . . . ?”

And I heard my lips responding, “At . . .”

Fifth beak-blow. It tore off his chin. The chin rolled down over his chest and his big white tie, cleaning off the dirt from the pedestal and leaving, in its place, a yellowish tooth that stuck there, shining like a topaz. Next thing I knew, the boiling up above had stopped, the coming and going of thick bubbles in the triangular nose hole subsided, the eye thread broke, and the chin hit the floor with the sound of a drumbeat. Then his two thin hands fell limp at his sides and from his sharp nails, pointed inertly toward the floor, fell ten drops of sweat.

There was a low whistle. A death rattle. Silence.

My uncle José Pedro passed away.

The wall clock showed 10:03 and 56 seconds. The scene had lasted 1 minute and 8 seconds.

After this, the green bird remained suspended for an instant, then spread its wings, shook them violently, and rose up. Like a kestrel over its prey, it hovered motionless in the middle of the room, the fluttering of its wings making a clicking sound like drops of rain on ice. And the pedestal, meanwhile, swung in time with the pendulum of my wall clock.

Then the creature flew in a circle and finally landed, or, rather, set its ebony foot on the table, and, turning its glass spheres once again to the bust of Arturo Prat, fixed them there in a still, infinite gaze.

It was 10:04 and 19 seconds.

On the morning of February 11, my uncle José Pedro’s funeral rites were performed.

As we carried the casket to the hearse, we had to pass by the window of my study. I took advantage of my companions’ distraction to glance inside. There was my parrot, motionless, his back to me.

The enormous hatred emanating from my eyes must have weighed on his back feathers, especially if we add to this weight—as I believe we should—that of the words hissed from my lips, “I’ll get you for this, foul bird!”

Yes, it must have felt it, because the bird quickly turned its head and winked an eye as it started to open its beak to speak. And since I knew perfectly well the question it was going to ask me, I also—to forestall the pointless query—winked, and gently made a slight grimace of affirmation that, translated into words, would be something like the following: “At your service.”

I returned home at lunchtime. Sitting alone at my table, I missed my dear uncle’s languid, moralistic chats, and always, day after day, I remember them and send a loving thought toward his grave.

Today, on June 12, 1934, it has been three years, four months, and three days since the noble old man passed on. My life during that time has been, for all who know me, the same as the one I have always led. But for me, it has suffered a radical change.

I am more complacent toward my fellow men, for whenever they require something from me, I bow and tell them, “At your service.”

Toward myself I have become more affable, for, facing any task of any sort, I imagine said task as a grande dame standing before me, and then, bowing toward the empty air, I say, “Madame, at your service.”

And I see the lady smile and turn to walk slowly away. With the result that no task is ever completed.

But in all else, as I’ve said, I’m the same: I sleep well, eat with gusto, walk happily through the streets; I chat with friends quite agreeably, I go out carousing some nights, and there is, I am told, a woman who loves me tenderly.

As for the green bird, there it is, motionless and mute. Sometimes, every once in a while, I give it a friendly wave, and in a hushed voice I sing to it:

I have seen a green bird

in rosewater bathing.

And in a crystalline vase

a carnation whose petals are falling.

But the bird doesn’t move, or say a word.

Published